GAČR 2025: Willi Pabst’s team aims to refine methods for glass phase determination

Determining the glass phase in silicate ceramics and refractory materials is crucial for understanding their properties, yet current methods often lack precision. Supported by the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR), Professor Willi Pabst’s research team aims to bridge this gap. By combining X-ray diffraction, computational modelling, and critical analysis, they strive to provide more reliable data for both research and industrial applications. What challenges do they face, and how could their findings shape the future of materials science?

How would you describe your project to a layperson in a few sentences? Why is it important?

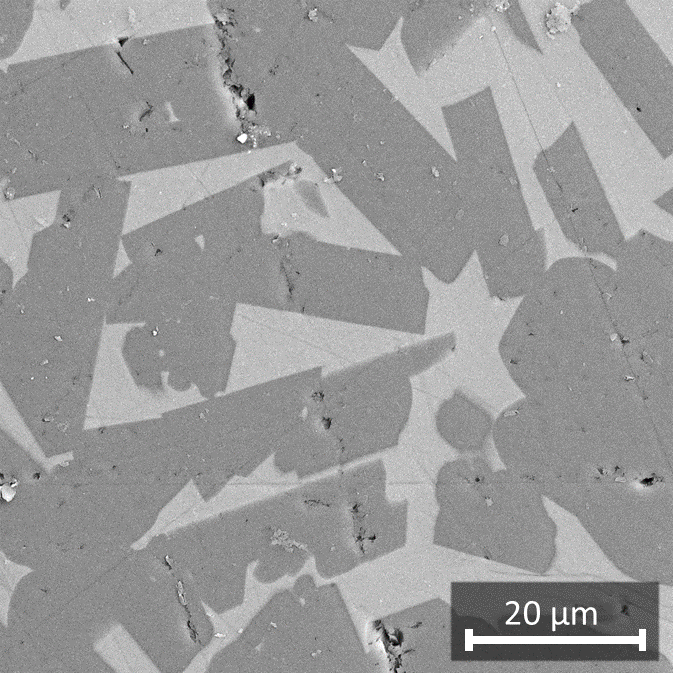

As the project’s name suggests, this research focuses on determining the glass phase (or more precisely, the amorphous phase, primarily its amount, but also its composition) in silicate ceramics and refractory materials. The most important method for this purpose is X-ray diffraction (XRD), commonly used to characterize crystalline phases. Quantitative determination of the content of glass phase using XRD is much more complex than for crystalline phases, and I believe that many researchers who uncritically rely on textbook procedures do not perform XRD accurately enough to use their results in further calculations, specifically, predicting properties—in our case, mainly elastic and thermophysical—which is our main goal. If accuracy is not guaranteed, the information about the glass phase is only an optical embellishment in articles but is essentially useless, just as a tomographic 3D image of microstructure essentially only has aesthetic value if you are not able to predict the effective properties of a given material from such an image. The second half of the project title refers to this fact.

What inspired you to choose this topic? Was it a specific challenge you wanted to address, or a kind of natural continuation of your previous work?

It is a continuation of previous research. One could even say that it is, in a sense, the last piece of the puzzle that we are still missing in this particular area of our work. As part of these research efforts, we first (more than 20 years ago) critically checked the literature about analytical predictions of effective properties. We found many fundamental errors in scientific tradition and common teaching which unnecessarily burden students with outdated concepts. Then we intensively dealt with image analysis based on stereology, which is of course necessary for the quantitative characterization of microstructure (including tomographic 3D images). Over the last decade, we have also intensively devoted ourselves to numerical modelling, i.e. the prediction of the effective properties of materials in cases where analytical solutions are not available. The only thing we have relied on so far was phase analysis. This has to be understood in the sense that one has to start somewhere, i.e. with a working hypothesis. We now want to test this working hypothesis more deeply and investigate to what extent phase analysis from other researchers or other research institutions can really be trusted, quantitatively. There is no doubt that we will discover many inconsistencies in today’s literature and I hope that we will be able to point out errors in this area and take down some scientific tradition myths. So far, we have succeeded in doing this many times in the areas that we have investigated more closely.

What is the main goal of your research?

The main goal of our research (if we are talking exclusively about this project) is—using a multi-method approach, i.e. a combination of various methods and calculations (which ones, I will not reveal yet)—to build such a solid foundation for the determination of the glass phase that it can really be used to predict the properties of materials containing a glass phase in addition to crystalline phases. If we are successful, the findings from this project will of course also appear in the classroom, where I consider it important to tell students that not everything they learn from textbooks and high-impact journals is necessarily correct. I am convinced that the best students—and these should be the main concern for a university—will be able to appreciate this.

What do you think captured the selection committee’s attention the most?

I have no idea. Perhaps only that I have assembled a team that includes experienced research matadors (Eva Gregorová, Petr Bezdička) and truly top doctoral students and post-doctoral researchers who are among the best at UCT Prague. Key members of this project are primarily Petra Šimonová and Lucie Kotrbová (alongside such renowned names in the field as Tereza Unger Uhlířová; Vojtěch Nečina; and Soňa Hříbalová, a Fulbright-Masaryk scholarship holder).

Will the project lead to any specific applications or technologies?

It depends. Applications and technologies come and go. Do not expect direct applications in the energy or national defence sectors. In today’s era of collapsing globalization, it is important to carry out this truly relevant applied research outside of grant projects that require more and more “open science”. Therefore, in this project, I am adhering to the original mission of the Czech Science Foundation (CSF), which is basic research. For me, this project is primarily an opportunity to investigate somewhat deeper an area that naturally interests me as a trained mineralogist and crystallographer. We will immediately apply the procedures developed in this CSF grant to materials that we are currently systematically investigating within the Jan Amos Komenský Operational Programme OP JAK MATUR project, i.e. refractory materials for thermal energy storage. I hope that we will be lucky (as with most previous grants) and discover something fundamental. Perhaps we will be able to propose alternative or complementary procedures that are more or less universally applicable that can then become part of modern research activities and modernized instruction in this area. My hope is that the methodology developed as part of this project will be so universally applicable that it can serve all scientists and engineers who need truly serious and reliable quantitative information about the content of the glass phase.

What makes your project unique? (For example: Does it utilize any unique tools or technologies? Will new ones need to be developed?)

Perhaps the complexity of this project. There are many groups in the world that deal with X-ray diffraction and the determination of the glass phase. That’s fine, and of course we will also learn from them. However, I believe that few groups in the world do such comprehensive research that they use the results obtained for the determination of the glass phase to predict the effective properties of multiphase materials. Our results should prove useful in that context. The uniqueness of the project is definitely not in terms of instrumentation. Unfortunately, we do not have the money for unique instruments. This project is therefore exclusively based on critical thinking, know-how with a pinch of courage, and the hard work of the team members. The methodology developed as part of this project should be general enough to be applicable for every scientist and engineer dealing with X-ray diffraction, regardless of whether they work on a synchrotron or on the cheapest laboratory diffractometer. At the same time, our intent is to alert scientists and engineers involved in property prediction that the glass phase can have a decisive influence on properties.

With whom are you collaborating on the project?

With one of the greatest Czech experts in the field of X-ray diffraction, Petr Bezdička (Institute of Inorganic Chemistry of the Czech Academy of Science). I appreciate his enthusiasm, diligence, and willingness to try new things.

What obstacles or challenges do you anticipate during the project? Do you already have strategies for overcoming them?

Our work will undoubtedly be full of challenges and potential obstacles. Our basic strategy is that we will start with simple, two-phase systems and gradually work our way up to more complex, multi-phase ones. Of course, I cannot promise completely new discoveries in advance, but I am optimistic that we will advance the reliability of XRD results in this area a little further, which will help everyone. Only the departure of key team members, especially doctoral students Petra Šimonová or Lucie Kotrbová, could significantly impact the project. To be honest, an average doctoral student who merely follows scientific traditions and established procedures would struggle with this work. It requires not only diligence but also critical thinking, which is why I have never taken on a doctoral student whom I have not known since s/he was an undergrad. Anyone who does not have this kind of background would have a hard time navigating a project like this one. I have no strategy for dealing with students who fall behind in this respect.

What brings you the most joy in working on this project?

That I can give my doctoral students Petra Šimonová and Lucie Kotrbová an opportunity to demonstrate their abilities, which I greatly appreciate. I have never had a better team. The project itself is, of course, close to my heart since I’m a trained mineralogist / crystallographer. I am returning to my roots, which is something I have never had time for yet, but I digress.

What, theoretically, should happen with your research after the project is completed?

If we manage to develop a reliable procedure for determining the glass phase in multiphase materials, or to propose new procedures, then we would, understandably, apply the new methodology to all our materials in subsequent projects in the future. We did the same with generally valid results with all our previous projects (e.g. new analytical predictions, new numerical predictions, new procedures in image analysis), which we now use as standard practice in our research activities (precisely because they are generally valid—and not only for one specific material). It should be recalled that this is the last piece of the puzzle for us in this area. That is, if we are able to more reliably determine the content and composition of the glass phase (in addition to crystalline phases), we will even be able to better predict, for example, elastic properties and thermal conductivity based on phase composition and microstructure (including porosity). I assume that the results from this project will then also become part of my teaching the Master’s course entitled Characterization of Particles and Microstructures. In my opinion, it is important that students take away from our lectures at UCT Prague something that they will not learn elsewhere.